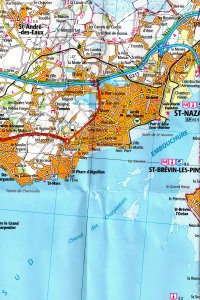

The fourth day of this trip was the most difficult so far. After the brilliant sunshine of the previous day, the grey, wet morning, as I looked out of the window of the Hôtel Marini came as an unwelcome surprise. I set off at around nine, found the Vélocéan cycle-track that – according to the tourist information and the colourful maps produced by the relevant tourist-offices – runs along the sea front, and followed it along the coast towards Saint Nazaire. The further east I went the stronger the wind became, the greyer the sky and the heavier the rain. By Saint Nazaire, I was already completely soaked and resigned to continuing that way for the rest of the day.

The Vélocéan cycle-track from La Baule to Saint Nazaire resembles cycle tracks in England – it’s more an idea in the mind of a planner than a reality. It is a matter of a few symbols painted on road-surfaces and a few signs along the road. At least the traffic density is less than on the main roads, but there are cars and lorries nonetheless and as with drivers everywhere, a significant percentage of them are either unaware of one’s presence as a cyclist or determined to show their disapproval of one's existence. Moreover, as always, the twists and turns required to keep off the main roads lengthens the journey considerably. Nevertheless, I was reasonably content to follow this route until, that is, it took me over the Pont Saint-Nazaire.

Finding the way onto the bridge was not at all obvious. It was as if the Vélocéan cycle-route became rather uncertain of itself at that point, or as if those responsible for it were a little reticent about indicating that it led across the bridge on a motorway-style carriageway shared by traffic travelling at high speed. From below, the bridge arches upwards to an impressive height. The gradient is not all that stiff, but it just goes on and on.

It is an enormous structure that spans the Loire estuary and is therefore exposed to all the foul weather that the Atlantic can throw at it. And on this particular day, the Atlantic was throwing its best. Even at the bottom, once I got out of the shelter of the buildings, the wind became a serious problem. It was an onshore westerly that was whistling directly from the right as I began the ascent. As I got higher, the wind’s strength increased progressively, until it became simply impossible to remain in the saddle. The so-called cycle-track is no more than a painted white line on the road and the wind constantly forced me to veer in front of the traffic roaring up behind me. Horns were constantly being sounded as my progress became increasingly erratic. Finally, I was forced to get off the bike and push it. But this, too, became more and more difficult as I approached the summit of the bridge. Towards the top, the gusts of wind were so powerful that I was obliged to hang onto the balustrade and try to make progress between each rain-loaded blast. At the apex of the bridge’s parabola, the wind was so powerful that breathing was difficult, my clothes were flapping wildly and remaining upright with the bike demanded every ounce of my strength. The traffic slowed noticeably as it approached the top of the bridge – which was one small mercy. The lorries in particular were clearly having great difficulty in maintaining a straight line. I had hoped to be able to get back on the bike when the descent began, but this turned out to be too dangerous and it wasn’t until I was well down the other side that I was able to get back in the saddle and ride. The two-mile stretch of the bridge had taken me over an hour to cover. I’m not a feeble individual, but I was exhausted by the experience and left wondering whether on an off day I might not have got into serious trouble.

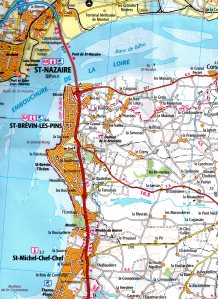

From the bottom of the bridge on the south side of the estuary, progress became a little easier thanks to the protection offered by the buildings. The Vélocéan cycle-track, however, remained uncertain of its own identity and consequently difficult to follow. I managed to stick to it through Saint Brévin-les-Pins,

Saint Michel-Chef-Chef (where the coast is littered with fishing cabins on stilts)

Pornic and Bourgneuf-en Retz.

At Pornic, a reasonably scenic little place, the weather looked briefly like perking up, but the respite was short-lived and it closed in again.

But at Bourgneuf I lost the Vélocéan track altogether and took to the roads. I would have had to use the roads anyway, at some point because my accommodation for the night was a few kilometres away to the east of Beauvoir-sur-Mer at a place called La Guillemardière.

This road-trip, however, was the most dismal bit of my journey so far and probably one of the most dismal bike-rides I’ve ever had. The road to Bouin led off into the Marais Breton, a flat area of salt marsh to the south of the Loire estuary. The wind, driving rain and the leaden skies combined to make this a most depressing experience. There’s something coldly desolate about marshland in foul weather. The cries of the birds and the gurgling of the channels that criss-cross the entire region has something unrelievedly melancholy about it that, for me, simply made the already difficult riding conditions vastly more uncomfortable. It was a matter of gritting the teeth and grinding onwards, sustained by the hope of the opportunity to change out of wet clothing, dry my gear and get a hot meal. If I had known what was awaiting me at my destination, I would certainly have abandoned these plans and stopped at a hotel on the coast. For anyone planning on following a route similar to mine, I recommend avoiding the place I chose as the staging-post for my fourth day. [ http://www.laguillemardiere.com/ ] It was a huge mistake: too far from the cycle-trails, of very poor quality and, for what it was, overpriced.

The light was fading a little as I approached my destination. It proved a little difficult to find La Guillemardière according to the directions e-mailed to me by the proprietress and nothing in the way of signposts identified it. Having finally located it, however, I began to wish I hadn’t. I found it after a particularly depressing and desolate ride through the marshlands flung around by the wind and drenched continuously by the horizontal rain. As I approached the group of low buildings that composed the gîte my spirits, rather than being lifted by the sight were driven down by the generally dilapidated and unwelcoming air of the place. I had to ask directions of a local who eyed me suspiciously as if he had rarely had the opportunity to encounter any other human beings other than his own rather stunted kind.

I finally knocked on the door of La Guillemardière and was greeted by a rather unfriendly character who announced that he was not in charge of the establishment, but would show me to my accommodation nevertheless. He conducted me to a long, low building at the back of the property. This was a series of very Spartan rooms, the last of which was to be mine for the night. He opened the door pointed me inside and and then made to leave me to me own devices altogether. I was beginning to feel a little peeved and determined to delay his hasty disappearance. I asked about drying my clothes and was told rather brusquely that I could put them on the washing-line. This response was exactly not what I wanted to hear after the ghastly day I had had. I told him straight that I needed proper drying conditions, warm dry air and the chance to air my things. He pointed me to a little shack that contained the water heater and said rather grudgingly that there was a little warmth in there and that I could hang my things up in there if I wanted. I was beginning to become irritated at the clear absence of hospitality in the bloke’s manner and since he obviously wanted to clear off as quickly as possible, I began to wonder whether I would be getting a meal at all. I broached the subject and learned that I was not expected for dinner and that I would have to get my own meal. At this, I started to get seriously annoyed; and he noticed. He quickly pointed out again that he was not in charge and having promised to send me the lady who was, he disappeared leaving me to settle in as well as I could.

The accommodation was of the most Spartan variety imaginable and in the cold, damp conditions in which I arrived, distinctly unwelcoming. The shower was located in a draughty wet-room distinctly reminiscent of the school showers of my childhood, primitive and comfortless. Since I had nothing from which to make an evening meal, I began to resign myself to a cold, solitary evening in a joyless hovel and to the prospect of putting my wet clothing back on in the morning. I toyed with the idea of simply leaving and finding a hotel, but the idea of getting back in the saddle after the day I’d had was unimaginable and I gave it up. I stood around disconsolately in the damp wind and wondered at what time I should go to bed. I was standing thus when the lady proprietress arrived. She could see from my face that I was not happy and inquired immediately whether I was OK. I explained my problems – wet clothes and no dinner – and she immediately turned out to be completely different from the chap who had opened the door to me. She showed me into the laundry where there was a number of drying machines and invited me to use them. She also invited me to share her own evening meal, even though she had understood from my e-mails to her in the course of booking the establishment that I had said I would not be needing one.

This of course changed everything for the better. I put my wet things in the dryer and joined the proprietress and the chap who let me in – who turned out to be her partner and fellow-sculptor – for dinner in their house. Dinner was an excellent omelette and a potato-pie – a local speciality – washed down with a decent Muscadet with cheese and fruit to follow. The hostess turned out to be a reasonably entertaining lady and the bloke - apparently her partner - thawed out and became almost human.

I went to bed in the Spartan shack reasonably content after the day’s disappointments.

No comments:

Post a Comment